MOVE BEYOND THE DEADLOCK

AD: Through the last years you have loudly sounded the alarm, unapologetically describing global heating as a “threat to organized human life on earth” en par with nuclear war. In your book with Robert Pollin, Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal (2020), you point out that the threat of global heating is doubly universal: it affects everyone and is also – in practice – universally denied.

Politically, we rely on our perceptions of what is necessary and what is possible, and these perceptions are often very distorted by rhetoric and demagoguery. If we deny the facts, we can deny that counteraction is necessary. Alternatively, we deny that radical action is possible, because it conflicts with various interests and interest groups. How can we move beyond this deadlock and mobilize in an effort that corresponds to the danger?

NC: It is very hard. In the United States, one problem is that the Republican party, which may very well take Congress in the next election already holds the court system is a hundred percent denialist. They just reject everything. Biden’s new program – which is not insignificant, but insufficient – meets a hundred percent opposition: they would not consider it. That makes it very different. And that of course reaches down to their voting base. They hear their leaders, they read Fox news. All of them are just debunking, saying climate change is just some liberal hoax – and the effect is they don’t take it seriously.

So how do we have a sane and humane response to the crisis? There are no magic keys. There are old answers. They’re the only ones. We can repeat them. They work with time and effort. There is no way around them. The first is to educate the population, to get the population to understand that we are facing a major crisis. That’s quite a problem. Let’s take the United States which I know best, and which is as far as I know studied in most detail and is the most important case – the richest and most powerful state in world history. What happens in the United States will largely determine what the outcome of this crisis will be.

There happens to be a Yale University – detailed studies of popular attitudes to climate change. These are careful, reliable studies, the most recent was released a short time ago. The design of the study was to present Americans with 29 choices and ask them, ask people, “How do you rank them? For determining your vote in the upcoming election?” It divided people in Republicans and Democrats. Overall, among the whole population, global warming, which was one of them ranked 24th of 29. Among moderate republicans it ranked 28th, among other republicans, it ranked 29th. That tells us something about the gap that needs to be overcome. Among democrats, it ranked higher, but nowhere near high enough. It should be number 1 or maybe number 2. The other one that should be at the top wasn’t even listed. There was no question saying “What about the threat of nuclear war?”. That wasn’t even among the list of 29 urgent concerns, so low down that the experimenters didn’t even think of including it. Those are the two issues that will determine whether humans, human society, survives or not in the near future. One of them is not even mentioned, the other is so low that it is disastrous. That tells us the work we have to do.

AD: Lately, you have spoken about how NATO has pledged to defend fossil fuel infrastructure and you’ve also talked about Pakistan and India who are mired in a military escalation involving nuclear threats, while they lose out in the struggle against global climate overheating and urgent measures to counteract global overheating.

What would it take for global heating to be acknowledged as a supreme security threat? I’m not suggesting that we leave it to the army, but pragmatically, what are the chances of such a line of argument winning through in the public discourse?

NC: Your comment about leaving it to the army is unfortunately appropriate. They are the ones doing something about it. The military is concerned, Pentagon in particular is concerned about the security threat of global warming and is devoting resources to it. So, the Newport naval base and other major naval bases will probably be flooded in the not distant future, so the military is undertaking expenses to preserve the military base. The military is generally concerned, in fact running exercises out of fear that as global warming increases it leads to violence, disruption potentially very severe conflicts where the military will be called in to respond to them. They’re working on measures, and you can see films featured on the Pentagon website that show how the military will respond to urban disorders and uprisings that will arise from the devastating effects of global warming. It’s not what you’re talking about, but it’s what’s being done.

Of course, now there’s total hysteria about the enormous military threats that the US is allegedly facing from Russia and China. Until that can be dealt with in some sane fashion, it’s going to be very hard to move towards the funding that’s necessary as Robert Pollin points out, which as he also points out, it’s not very great. What he’s calling for is a small percentage, couple of percent of the gross domestic product, actually less than the Treasury Department spent in bailing out major businesses who were harmed by the COVID crisis. It’s not out of sight by any means. But as long as this huge wastage in military spending and lack of concern, inadequate concern about the climate, it’s going to be a lot of work to change.

CARICATURE OF CAPITALISM

AD: For a perspective on what is possible, when the threat is acknowledged as necessary, Robert Pollin’s estimate is sobering: As you mention he says 1 or 2% of GDP would be sufficient to transition at least until 2050, while – as he points out – during World War II, the spending for the war effort went up to 48% of the GDP. When Pollin lately spoke about Biden’s new bill, touted by some as a turning point in U.S. climate policies, he says it does about 10% of what is needed in annual spending. The necessary annual spending for climate change transition would according to him cost about 400 billion.

NC: It’s pretty amazing. In fact, even the solutions that are being proposed, as in Biden’s, are framed within the insane capitalist model. If you want to get something done, you have to bribe corporations to do it instead of just giving them directives, as they did in the Second World War. They just told them, “This is what you’re going to do.” So yes, very effective, isn’t it? An industrial planning program. But now you have to find devious ways to see if you can get them to do it. It’s difficult, as I’m sure you have seen. The Supreme Court, just in one of its recent, very reactionary judgements, sharply limited the capacity of the Environmental Protection Agency to monitor and control drilling and use and exploitation of producing CO2. Actually, some of the things that are going on are almost surreal. I mean, if somebody were going to try to write a caricature of capitalism, they couldn’t do better.

As you know, the Arctic is heating very fast. It’s very dangerous. It’s getting to the point where permafrost is beginning to evaporate. There are astronomical amounts of carbon stored in the permafrost. One of the fossil fuel companies announced that it has developed a technique to insert devices into the permafrost which will harden it and retard its melting. The reason they’re doing this is so that they can get more oil out of it from drilling, and therefore that’s the problem. We can harden. It won’t melt as fast, so we can drill. That’s the capitalist ethic. We need to find a way around it. This was crucial during the Second World War, where it was just abandoned in a war economy.

AD: States of exception seem to work both ways: The Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to new arguments of necessity and imperatives, in support of ramping up fossil fuel production. The pressure feels very real as Europe in particular is striving to cover its energy and gas needs without Russia. Some people, like Bill McKibben, has argued that it is a golden opportunity to build alternative energy systems, but building new systems is slow and cumbersome, and so far, the conflict has meant a boost for the fossil fuel industry. But there are other routes to climate action that are possible: For instance, you’ve highlighted – as many do in our times, that meat production and consumption should go down drastically and that we need to change agricultural practices.

NC: We have to learn to move towards more plant-based diets and that has to be done in a way which allows sustainable agricultural production, not pouring fertilizer over the land, destroying it. It’s not a small task.

AD: What strategies can be made to bear on international agricultural companies such as Bayer and DuPont, those few players that control fertilizers, pesticides and that control seeds – or against Tyson and Cargill who are major actors in factory farming in the US? Like the oil companies they are phenomenally powerful. Corporate power is a crucial hurdle for effective climate policies. Do you have any hopeful prospects for limiting their – or do you have any examples as to how it can be done?

NC: There are lots of prospects. Everything from consumer boycotts to infiltrating the management structure. I don’t know about Norway, but in Germany, mostly theoretically, there’s co-determination. 50% worker representatives with enough changes in popular consciousness could change the way corporations’ function, basically move towards taking them, turning them into popularly-run organizations with worker control decisions, decisions as to link to communities, what kind of a world do we want to have? It’s not just how many super yachts… Do we want to be in some executives’ harbor? I don’t think this is impossible.

AD: Given that the timeframes of the climate crisis gives us very little time to change the system, how can we do what is necessary within the existing capitalist framework?

NC: The fact of the matter is, like it or not, we’re not going to change the basic framework of the institutions of state capitalism in any timeframe that’s relevant. You can talk about it, try to create a background for maybe initiatives like worker cooperatives and so on, which is important, all important. But it’s not in time. So, it is going to have to involve state capitalist institutions. But we can hope that with enough popular pressure, enough popular education, there will be the kinds of mounting pressures that have led governments to at least do something and have led the fossil fuel companies to at least make some gestures.

Actually, this is one of the things Bob Pollin pointed out: that if you look at the total value of the fossil fuel industry, the government could buy it up, all of it, and turn it to renewable energy. It’s within the scope of financial possibility. Nobody talks about it, of course, but it could be done. In fact, it’s not really as remote as people think.

So go back to the Great Recession in 2009. Obama pretty much nationalized the entire auto industry. They were all collapsing. The government essentially bailed them out. Well, there were options at that time. One option was the one that was taken: hand it back to the old owners, maybe some new faces and have them produce cars for more traffic jams and more destruction of the environment. Now that was done. There was another option, and had there been popular understanding, popular support, could have been taken. Take the old auto industry, hand it over to the workforce communities, have them produce mass transportation, efficient mass transportation, which is very lacking in the United States.

If you look at the total value of the fossil fuel industry, the government could buy it up, all of it, and turn it to renewable energy. It’s within the scope of financial possibility. Nobody talks about it, of course, but it could be done.

OTHER PLAYERS, SOLIDARITY AND CLIMATE INTERNATIONALISM

AD: As you emphasized, the US is in a particular position internationally, being so powerful. It means it’s very difficult to change or influence it, and also that changing the US is supremely important. But what about other power players internationally? Do you pin your hopes on any other state internationally to push forward for international collaboration in climate mitigation and innovation?

NC: This is an interesting question. The next biggest power to look at is China. It’s a huge economy. It’s not the United States, but in purchasing power parity, it’s about comparable to the US. Enormous capacity, extraordinary internal problems. In fact, climate is one of them. Right now, they’re suffering from a drought of a kind that hasn’t happened for 500 years. You can walk across the Yangtze River at this point.

But they do have their way in the lead in renewable energy, more in quantity and sophistication, electrical vehicles. They have plans to reach carbon neutrality by about 2060 or so. They are still constructing coal plants. It’s kind of a mixture. In the current economic doldrums, their economy’s not in great shape by Chinese standards. They are turning to more fossil fuel energy, same time they claim that they’re moving ahead on schedule to sharply reduce or perhaps eliminate fossil fuels.

There are other decent signs. Like, the US government is hopeless under the control of the Republican party, but states are doing things, like California, which by international standards is quite a large country, is planning to eliminate all fossil fuel-based automobiles within a couple of decades. That’d be 2040 or so. If they do that would have a big effect on the whole industry because California is such a large consumer that the auto industry gears a lot of its production towards California consumption. So maybe that’ll give a boost for developing a usable electric grid and more production of electric vehicles. There’s an incredible backlog for them. I just read today, in fact, that Ford Motor company has an electric version of one of these huge monsters that everybody likes to drive, the Ford Lightning, I think. A ridiculous object. Anyhow, they have a three-year backlog for it. They just can’t produce them fast enough. That’s the kind of pressure that may mean something.

Another thing, which actually Bob Pollin was involved in, we may have talked about, is that he’s managed to get fossil fuel workers unions in many states, including California, to advocate a transition program. I think half a dozen unions in California, others in Ohio and West Virginia, fossil fuel producing states, to including the United Mine Workers, to say they’d favor a transition program in which workers in the fossil fuel industries would be helped to move out of the industry and into things like renewable energy. That could be other kinds of pressure.

AD: Solidarity and internationalism seems to be a receding trend in a time where it is needed more than ever. The question of internationalism is interesting also because you spoke about the oil and gas unions, and you’ve been referring to Rosa Luxemburg and her work on international movements among union workers. Do you see that as a possible route for climate mitigation? Workers around the world united, somehow, again?

NC: It’s a nice idea. It won’t happen if there are international conflicts. A prerequisite for all of this, in fact, a prerequisite for survival – we can’t forget this – is accommodation among the major powers. If Russia, the United States, and China are at swords’ points, then we don’t have any hope. They have to accommodate. They have to overcome the conflictual relationships and turn to cooperation and accommodation for Eurasia.

Germany has had a moderately decent record in trying to move towards renewable energy. That’s of course reversed with the current crisis. But I find it kind of hard to believe that Europe altogether and the intricate German-based production system in Europe, reaching from the Netherlands to Slovakia, seems to me hard to believe that they’re going to agree to hang on to Washington’s coattails instead of moving towards some kind of accommodation with Russia, which they desperately need. It’s a very natural relationship. Even for sustainable energy, Germany is going to rely on Russian minerals.

Quite apart from the very close interactions with Russia, Europe is going to surely want to break into the China-based Belt and Road initiative, which is an enormous system of development. It involves big investments and leads to the China market, which is already Europe’s biggest export market outside the US. I just can’t see them just keeping away from that in order to follow US demands. So, I suspect that these arrangements will break down sooner or later and may have a big effect.

AD: Which would shift the global balance of power, perhaps, more away from the US? You’ve written and spoken much about US vetoes to international treaties through the years. As the need for international cooperation and solidarity grows, it seems to become increasingly difficult even for the UN to secure a meaningful cooperation. Do you see any movement toward a new and stronger internationalism, even beyond the nation-state?

NC: There are popular groups, World Without War, and many others, but nothing of significant scale. What you describe is… Oh, there aren’t any words for it.

The last couple of days, I have had several discussions, talks and interviews in South Asia, West Bengal, Bangladesh, Delhi, Pakistan. It’s madness. South Asia is becoming unlivable. In India, about maybe 10% of the population has air conditioners and there are places where the temperature is reaching 50 degrees Celsius with poor pilgrims living in dirt huts and humid areas. You just can’t survive.

AD: And lately, ever more destructive floods…

NC: It’s getting worse, of course, in both Pakistan and India. In other seasons, diminishing sources of water, common sources – as the glaciers melt. And they are both nuclear powers. They’re putting their resources into preparing for war to try to, among other things, keep control of the diminishing water resources – without which South Asia will become unlivable, literally.

As for Europe, ever since the Second World War, there have been competing visions. There was the kind of Gaullist vision of an independent Europe, a third force in world affairs. It transcended into Mikhail Gorbachev’s common European home after the collapse of the Soviet Union. A region from Lisbon to Vladivostok with no military alliances, Russia and Europe as co-equals, no victors, no defeated, both moving towards kind of social democratic future: This was Gorbachev’s proposal.

Russia has in fact supported that. The US was strongly opposed to it, of course. Putin, last February, plunged a dagger into it by driving Europe into the pocket of the United States, a policy that’s criminal but also idiotic, even from his point of view. They were tentative, but not meaningless initiatives, primarily by Macron up to four days before the invasion. Read the transcript in the French press, La Plume. They didn’t reach a conclusion, but they weren’t totally inconclusive. There were threads that you might hang onto there. Putin ended it by saying, “Well, I’ve got to go off the go ice skating,”, kind of a gesture of contempt. But maybe with Western support, it could have gotten somewhere.

They’re putting their resources into preparing for war to try to, among other things, keep control of the diminishing water resources – without which South Asia will become unlivable, literally.

AD: Putin’s pressure on Europe through oil and gas supplies led to intensified extraction and increased demand for oil and gas from Norway, among other producers. It is true that it takes time to develop new technologies and roll out the systems. But money might be much more important. What role do you see in technology development, granted that public funding and subsidies are so important in developing, for instance, alternative energy?

If you look at the budgets for research and development of solar compared to oil, it’s minuscule, and it’s always been very small. In the US, and in general, do you think if more public money, a lot more was siphoned into developing all the technologies, that we could see a really substantial shift in a short time? That rapid change is indeed possible through public funding?

NC: Yes. No question. In fact, we just saw it with the vaccines. Incredible amounts of federal money came in. We had very rapid development of vaccines. In the case of Moderna, it was probably all federal money, both for the actual research and also for purchasing the output, which gave the corporation the incentive to produce it first. It’s kind of roundabout way to get things done, but it did get done when you have plenty of multimillionaires on your side.

YOU END UP WITH NOT BEING WILLING TO WORK FOR THE COMMON GOOD

AD: Talking about multimillionaires, you speak of in quite positive terms Jeff Bezos’ program for climate change mitigation, or rather the campaign that put pressure on him to do so. Will the 10 billion that he donated make a significant difference? Bill Gates is doing the same. It seems like they’re washing their hands and they probably are. But from a better-than-nothing-perspective, do you think there’s a lot more to gain in putting pressure on corporations and the ultra-rich?

NC: Well, you have to be very careful. I’ll give you an example. At the Glasgow Conference last year, the last international conference, you may recall that John Kerry, the US ambassador, came out with a very euphoric message. He said, «We’ve basically won. We now have the business world on our side.» What happened is that Larry Fink, who runs Black Rock [inaudible 00:41:10]. And he said, «We’ve now organized the investment community. “We have,» – I think he said – «$130 trillion,» or some astronomical number, «that we’re willing to, that we’re going to devote to climate change. How can we lose?»

One very good political economist, Adam Tooze, looked into it a little more carefully. He noticed the actual promise was, «We’ll be happy to invest in sustainable energy on two conditions. One, it’s profitable. Two, if it’s not profitable, the IMF will pay us off. So, if it’s riskless and profitable, we’re happy to do it.»

“We won”.

AD: What about corporate law? The US is particularly strong on laws for shareholders, and there’s this sort of mandate or an obligation to maximize shareholder profits, which must be a very strong driver toward pushing all other concerns aside.

NC: First of all, there’s nothing inherent in corporate law that requires that. You could perfectly well have corporations which are concerned with stakeholders, not shareholders. This has mostly developed since the neoliberal period. Of course, it was always there, but it became the top leading factor in executive management only since Reagan and Thatcher. That’s not built into the nature of the society.

We’ve been through 40 years of an assault that’s attempted to impose pure individual self-interest. It’s had a big effect, even in destroying the institutions of self-defense. Like, it wasn’t just by accident that Reagan and Thatcher began their terms by attacking the labor movement. That’s the means in which people can get together and work for their common interests. I’m old enough to remember this from when labor unions actually functioned. So, if I go back to childhood, the Depression in an immigrant family that had mostly unemployed workers, save my aunts who were in the ladies’ garment workers’ union. It wasn’t just wages. It was a life. They had cultural activities, educational activities, even a couple of days up in the countryside in the homes that they owned. It was just a whole community of life. That leads to a kind of solidarity and mutual support that manifests itself in political activity as well.

You did have mass popular support for the New Deal measures that kind of brought modern social democracy to much of the world. That can be recovered. It made good sense to try to break those systems so that people are alone, atomized. It’s kind of interesting to look at the ideology. You may recall one of Thatcher’s famous lines is «there’s no such thing as society”, just individuals alone on the market, which of course is a total lie. She understood perfectly will that for the rich and powerful, there’s a very extensive society: the chambers of commerce, trade associations; actually, the government, which they mostly control. For the rich, plenty of society. But for everybody else, you’re trying to survive somehow in the marketplace in a precarious existence. Things were done at every level to ensure this.

To talk about my personal experience, I taught at a university for 60 years. I don’t have a pension because pensions were limited in favor of investments in the market. So, you have stocks. One of the things that does is change your mentality. It means your keyed to the stock market, but not a person who just… I have a certain amount of security. I can do the things I want, but I have to make sure that the stocks are all doing the right thing. I’m the usual victim of the market. Everybody roped in very carefully to ensure that… don’t even talk, have nothing to do with each other. You end up with not being willing to work for the common good.

For the rich, plenty of society. But for everybody else, you’re trying to survive somehow in the marketplace in a precarious existence. Things were done at every level to ensure this.

AD: The situation gets rigged so that everyone bonds with the market, rather than showing solidarity with other people – not to mention future generations. Is this the main reason why there is so little commitment to curbing carbon emissions and fighting global heating.

NC: The situation in the United States is quite straightforward. The republican party is 100% denialist. They don’t want to hear anything. Basically, they were bought off. I’ve forgotten if we’ve talked about this, but what happened is pretty revealing.

If you go back to 2008, the Republican candidate was John McCain. He was kind of a moderate hawk, not crazy. He had a limited climate platform program in his campaign platform. There’s a huge energy conglomerate, private – the Koch brothers’ energy conglomerate – and enormous fossil fuel-based system, involving trillions of dollars. As soon as they heard about this, they went into action, and they launched a real juggernaut, a bribery of candidates and intimidation, threatening to run candidates against them and lobbying fake popular organizations to protest everything. Whole party sold out. All of them. Not a single one stood, and they haven’t changed since.

Now under Trump, it got worse because they’re all terrified of Trump because he has this mass base of worshipers who are violent, extreme, religious extremists. It’s kind of amazing: He’s a person of utter insignificance who’s managed to have an extraordinary impact on the country and the world. Remember the Republican party now, the main thing you have to know is how to go Mar-a-Lago and shine his shoes every once in a while, or else you get knifed in the back, and they all do it. Well, that’s half the political elite.

You look at the other side, the Democratic party, the sort of management of it, the mainstream of it is abandoned the working class about 50 years ago. They became a party of basically affluent relatively well-off professionals and Wall Street. They don’t do anything for the working class. They basically handed the working class over to their class enemy, which mobilizes them on what are called cultural issues: white nationalism, guns, abortion, anything with policies. That’s the political system.

Now there is something else. There’s the Sanders base, which is significant. He’s one of the most popular politicians in the country. He has this substantial base of mostly young people who are active, engaged, have some representation in Congress. Very hard for them to break through. They don’t have the money. Elections in the United States are mostly bought. It’s very hard to do anything without a lot of rich power behind you. But they’re there, and there is a popular base. That’s Biden’s program. He would never have had such a program if it hadn’t been through their activism.

POLITICS OF DENIAL

AD: So much of your work has to do with the media, and it’s unthinkable to have a global public sphere or even a national public sphere these days without good media. How can the problem be met in different nations of the world? Populism in India, for instance, and Pakistan, Putin’s Russia.

NC: I wish I had an answer. The media are unfortunately on the opposite side of the battle. The most viewed television channel in the United States is Fox News. It’s denial. The others sort of bring it up, but not significantly. It’s the same in India. The media are pretty much under the control now of the Modi government, the ethnic nationalist government, which is trying to dismantle the Indian democracy, which was a tremendous achievement after the British were finally kicked out. They want to dismantle it. The media are mostly going along. We know the reasons. It’s not anything particularly new. But it’s very hard to break through.

AD: The discussions about what is real and scientifically proven echoes in the confused rhetoric of what is necessary, possible and impossible politically. It could be said, as many do, that after the buyouts or the rescue packages to the banks in 2008 and after the measures against COVID, it’s kind of proven that a lot more can be done financially, if it is only perceived as being necessary. Why has the general experience with COVID made a greater impression on the general public in and on the political scene in the US?

NC: There’s a number of reasons. For one thing, there is a substantial part of the population that is simply anti-vaccination with all kinds of crazy reasons. It’s a pretty crazy country, remember? If you look at attitudes on some other things, it’s mind-boggling. Take evolution. When I was a student, I went to an Ivy League college in 1950. If an instructor wanted to bring evolution into the class, they’d open the class by saying, «You don’t have to believe this stuff, but you ought to know what other people are thinking.» Today, the pro-science groups claim to be encouraged by the polls. But if you look at them, it’s not very encouraging. By now, it’s true that about maybe 70 or 80% of the population say that evolution’s real. If you look at those, about 20%, believe in evolution, the rest say God gave it to us. The group that believes in evolution is relatively small.

AD: The case is similar with respect to antropogenic heating of the atmosphere. A poll by YouGov from 2019 showed that the number of climate deniers or radical sceptics in Norway was 8 percent, but what placed us at the bottom end of climate engagement internationally was the fact that 48% thought global heating is only partially caused by human impact. In practice, which means they’re on the fence about it – and this makes drastic measures very hard to orchestrate.

In a new poll from King’s College (PERITA), Norway came out worse, not better – the number of climate deniers being the highest in Europe at 24% and Norwegians stood out in every question in the poll as the most unconcerned and uninformed nation in Europe. We also did worst environmental attitudes and values, even in such questions as single-use plastics and recycling and when asked nearly half the people said they didn’t want to learn more about climate change.

NC: The biggest producer of oil in Europe… Could be a correlation. Anyway, that’s the situation in the US: The public base is not concerned. The party leadership just refuses to do anything.

AD: The problem seems to be that in Norway you can’t even dismiss it as corporate power: these are to a great extent state-owned companies – and in one sense, it is more a matter of the whole people being reluctant to giving up on the benefits and future revenue from oil extraction. What would be a sound policy and a sound point of argument in a situation like that – where voters elect politicians are prepared to dish out their oil resources for the economic benefit in the next decades, rather than doing what must be done to curb global heating?

NC: Basically, do you care if there’s a world for your grandchildren and for the children of tens of billions of people all around the world? If you don’t care about that, spend what you like. If you care about it, here’s what you have to do. It’s not that you’re going to get a difficult life. You get a better world, in fact.

AD: But granted that a very small percentage of the people believe in this as an actual disaster prospect, it is very hard to make sacrifices. Again, this to be a vitally important point. I guess that’s why you come back to the formulation, “The destruction of organized human life on Earth”. This is what is at stake, this is precisely where we’re headed: unless we act, we’re in for a horrible predicament with three or four degrees warming. Irreversible damage to the living planet, a partial or total breakdown of global civilization. Climate scientists say, “don’t go there!” – and it is still avoidable. But this is probably not how the majority of voters see things, even if they acknowledge anthropogenic global heating.

NC: That’s a barrier. You can’t minimize it. You have to bring people to see it.

We have to have a real change in the nature of the whole way society’s organized, perceives its options, committed to the common good instead of individual gain. I don’t think these things are impossible, but it’s a major change in the way we conceive of the world.

Maybe you need to put it in personal terms. It’s your grandchildren. Do you want them to live in a decent world or to be overwhelmed?

AD: The simple binary choice, the strong moral imperative reminds me of your references to Rosa Luxembourg. How do we keep our faith in moral responsibility and progress in common causes like the climate when the world slides into new antagonisms and wars?

NC: Of course, she was talking about a particular society taking over factories in Germany, specific problems, specific problems that happen to be different today, but the basic ideas have not fundamentally changed, I think. Basically, that we have to learn what she said: It’s going to be our common commitment to a viable life – or barbarism.

//

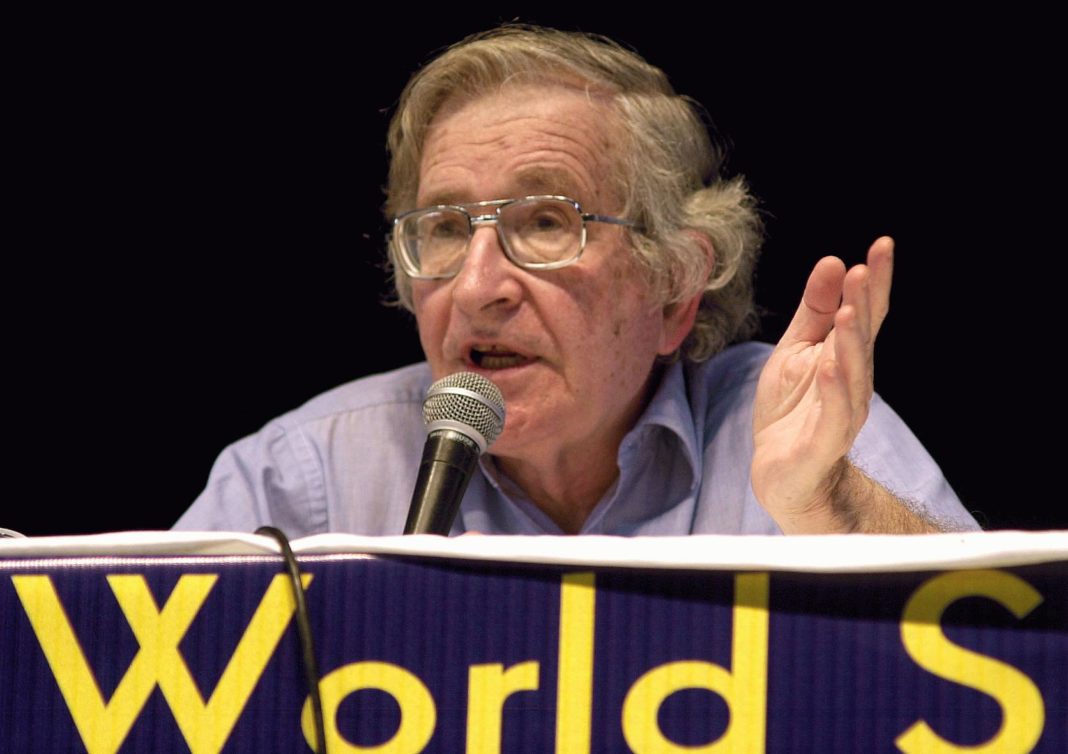

Noam Chomsky (93) is an American linguist, philosopher and social critic. Often quoted as the world’s leading public intellectual, his views and analysis have been influential for the critical left and through the last decade he has increasingly engaged with climate change issues, as in his 2020 book Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal – The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (With Robert Pollin). Chomsky has written more than 100 books, and he is one of the most cited scholars in modern history.

//

Anders Dunker works as a journalist and philosophical author, focusing on the environment, technology, and the future of the planet. His works includes a series of interviews with leading international environmentalists for the Norwegian journal Samtiden, that was published as Gjenoppdagelsen av Jorden (2019) and translated into English in 2021 as Rediscovering Earth (O/R books). Anders Dunker is also a permanent member of the NWCC’s Editorial Board.

Dette intervjuet er hentet fra nettsiden til Forfatternes klimaaksjon, utgitt med støtte fra Fritt Ord og Bergesenstiftelsen.